This post was originally published on this site.

In a challenge involving Vice President JD Vance, the high court could overturn a 2001 decision upholding an anti-corruption rule aimed at preventing wealthy donors from giving too much to a candidate

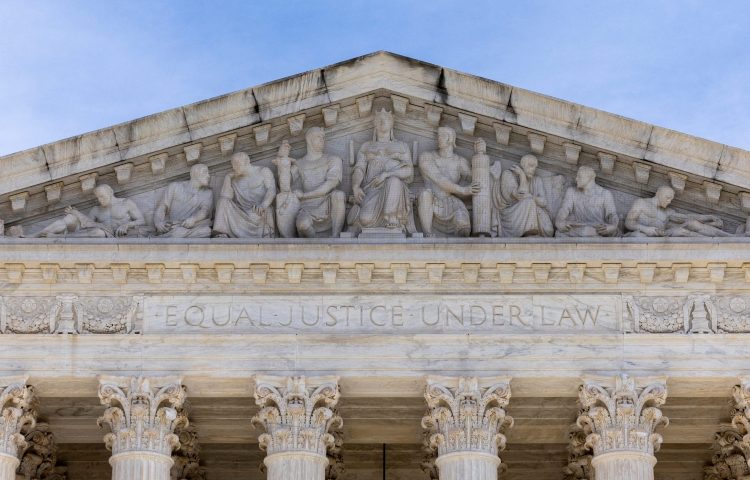

How the Supreme Court could impact the 2026 midterm elections

The Supreme Court ruled that Texas can use a congressional map drawn to give Republicans an advantage, with other states now following suit.

WASHINGTON − The Supreme Court could eliminate one of the remaining checks on money in politics in a case that worries advocates fighting the influence of deep-pocketed donors.

In a challenge involving Vice President JD Vance, the court will consider on Dec. 9 the Republican Party’s argument for overturning a 2001 decision that upheld a rule aimed at preventing wealthy donors from bypassing limits on what they can give candidates by funneling money through political parties.

Since that 5-4 decision, the court has become more conservative. And campaign finance law has changed, both by Congress and through other Supreme Court rulings striking down various rules as improper restrictions on “political speech” under the First Amendment.

Republicans argue the altered landscape means the court should now scrap the limit on how much political parties can spend in coordination with candidates for federal offices.

“That 5-4 aberration was egregiously wrong the day it was decided, and developments both in the law and on the ground in the 24 years since have only further eroded its foundations,” lawyers for the Republican Party told the court.

An off-ramp to an ‘inherently politicized case’

Former Sen. Russ Feingold, D-Wisconsin, who authored other campaign finance rules that have been partially overturned by the Supreme Court, wrote in a brief for the case that getting rid of the coordinated spending limits would be “the next step in the march toward allowing unlimited money to swamp American elections and drown out the will of the voters.”

But the court could also avoid the issue by dismissing the case after hearing it.

After President Donald Trump took office, the Justice Department stopped defending the federal rule.

The lawyer the court then appointed to argue in support of the rule said the justices don’t have to weigh in now because there’s no threat that the federal government will enforce the coordination restriction.

“That result would not fully satisfy everyone, but it offers a middle ground that respects constitutional values and exemplifies judicial restraint,” attorney Roman Martinez wrote, explaining how the justices could avoid “this inherently politicized case.”

If the court doesn’t agree, the justices could take another incremental step towards deregulating the campaign finance area, said Rick Hasen, a professor and election law expert at the UCLA School of Law.

“Or,” he said, “the court might use the case to more broadly call campaign contribution limits into question.”

Rule passed after Watergate scandal

The coordinated spending restrictions at issue were included in campaign finance regulations passed by Congress in 1974 in response to the Watergate scandal.

In a landmark 1976 decision about the entire campaign finance law, the Supreme Court said limiting some types of campaign expenditures improperly restricts speech. But the court said Congress could restrict campaign contributions if done to prevent corruption or the appearance of corruption.

When a party pays for an ad at the request of a candidate, the court later said in the 2001 decision being reconsidered, that expenditure has the same effect as a direct contribution to the candidate so can be regulated.

And because donors can give more to parties than they can to candidates, donors might use parties to get around the lower limits, increasing the possibility that a backer might expect something in return for the support, the court ruled.

High court hammers campaign finance rules

But since that decision, the court has taken a tougher approach to campaign finance rules in a series of cases, including a 2022 ruling that contribution limits must be backed with “actual evidence” that they will prevent corruption.

Republicans argue the evidence in this case amounts to, at most, “mere conjecture.”

Anyone seeking favors in exchange for donations would still be limited by how much they could give to the party. And mega-donors trying to influence elections are more likely to turn to the kind of political action committees the courts have allowed since 2010 that don’t have contribution limits, the GOP contends.

Size of political donations has ‘skyrocketed’

Their challenge was initiated in 2022 by Vice President Vance, when he was running for the Senate, along with former Rep. Steve Chabot, the National Republican Senatorial Committee and the National Republican Congressional Committee.

The Cincinnati-based 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the challenge, saying its hands were tied by the high court’s 2001 decision.

Marc Elias, an attorney for the Democratic Party, which backs the limits, said nothing has changed in the campaign finance system since 2001 other than donors are now writing bigger checks. He pointed to the joint fundraising arrangements that allow candidates to combine forces with parties and political action committees to solicit funds.

“We have seen the size of those checks skyrocket into the hundreds of thousands, nearing $1 million per person,” he said.

A GOP ‘bait-and-switch’?

Martinez, the lawyer appointed by the court to defend the restrictions, said that increase is in large part because of a 2014 Supreme Court decision getting rid of the limit on the overall amount one person can spend on political contributions. At that time, he said, Republicans argued that the coordinated spending limits they now want to eliminate would keep things in check.

The GOP’s latest challenge, he told the court, would not only complete their “bait-and-switch,” but would call into question many other campaign finance rules.

“The Court should not put itself in the business of deconstructing fifty years of campaign-finance law one petition, provision, and precedent at a time,” he said in his written argument. “Yet that is exactly where petitioners would take us.”

In response, the Republican Party said that while it’s “made no secret” of how it thinks all campaign finance rules must be scrutinized, the court doesn’t have to go that far in this case.

Given the lack of evidence of an actual problem the coordinated spending limits are intended to prevent, the GOP said in a written brief, a ruling striking down only those limits would suffice.