This post was originally published on this site.

With the start of 2026, one of the stalwart galleries in New York’s art scene, Sperone Westwater, is no more. Amid a legal dispute between its namesake principals, the 50-year-old firm shuttered before the clock struck midnight on January 1.

But the legal drama over the dissolution of Sperone Westwater Inc., a corporation established in 1975 by Gian Enzo Sperone, Angela Westwater, and the late German dealer Konrad Fischer (who exited in 1982), is not abating. In documents filed this week, Sperone expands on his claims of mismanagement by Westwater and rebuffs allegations that she made in late-December filings that he has long been out of touch with their business.

The battle began in August, when Sperone, 86, and Sandstown Trade Ltd. (an entity connected to his family that owns 50 percent of the company) initiated proceedings in a New York court to unwind its two assets: the Sperone Westwater gallery and its Norman Foster–designed home on the Bowery in Manhattan.

Lord Norman Foster, Angela Westwater, and Agnes Gund at Sperone Westwater on September 21, 2010, in New York. Photo by Ryan McCune/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images

The corporation’s “two directors are so divided” that “they do not even speak directly to one another,” the petition states, describing the situation as “a kind of parasitic deadlock.”

Amid the alleged decline of the gallery, Westwater was using “one very high value asset, the Foster Building, to subsidize the other unprofitable asset, the Gallery,” the petitioners contend. The partners had agreed that the gallery would pay $1.8 million in annual rent to the corporation (to generate income from their investment in the building), but it has not done so, according to court papers. Sperone and Sandstown are asking the court to appoint a third-party arbiter, also known as a receiver, to resolve outstanding matters.

Westwater, who is the other 50-percent stockholder, is asking the court to dismiss the petition and forgo the receiver, saying that the partners are not deadlocked and that Sperone and Sandstown are engaged in “a blatant attempt to extract every penny from the Corporation for their own financial benefit.”

On December 22, she fired off a memorandum to the court accompanied by several juicy exhibits, including a nine-page “term sheet” with details of winding down the gallery that Sperone’s filings say was supposed to remain confidential.

The agreement, which had been drawn up through mediation, details who gets what and when. If the partners can’t agree on all the terms, they are to select an independent referee to help them.

One example from the term sheet: The parties will receive 50 percent of the proceeds from the sale of the building and equally distribute 80 percent of the corporation’s cash reserves within 10 days after the execution of a settlement agreement. Also, the proceeds from art sales will be also evenly divided, “except that 20 percent of each artwork sale shall first be paid into a lockbox account, established jointly by the Parties, to be used for the sole purpose of paying any outstanding debts, liabilities, and taxes that are identified during the wind-up process under the below terms,”

Bruce Nauman’s work at Sperone Westwater at Art Basel Miami Beach in December 2025. Courtesy: Art Basel

Some items have already been handled. Westwater’s memo states that the gallery terminated employees and returned “nearly all consigned artworks to their original owners.” It also reveals that the parties have retained the brokerage firm CBRE “to place the Foster Building on the market and sell it to the highest bidder.”

She claims that she’s been “the only person responsible for the daily management—including all financial and employment decisions”—of the gallery.

Even before Sperone moved to Europe in 2016, he “had very little involvement in the Gallery’s operations,” she claims. “He would spend approximately 30-50 days at the Gallery each year and would appear only for openings and exhibitions. He was otherwise a largely absent partner.”

Westwater says that Sperone has not been to the gallery, or the United States, since relocating. “In fact, he has been so absent from the Gallery that Ms. Westwater has only communicated with him through his girlfriend’s email account and has had to ask her whether Mr. Sperone was still living since it had been so long since she had heard from him,” her filing says.

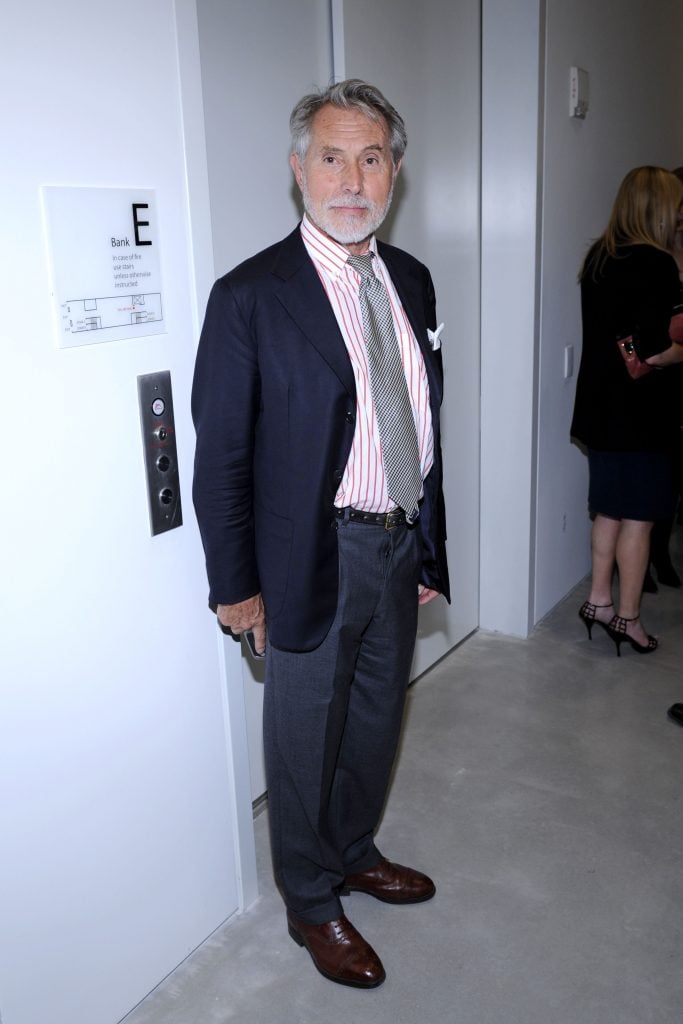

Gian Enzo Sperone at Sperone Westwater Gallery on September 21, 2010, in New York. Photo by Ryan McCune/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images

On Tuesday, Sperone and Sandstone responded to Westwater’s claims with affidavits and 24 exhibits that include emails, invoices, and a financial analysis of the gallery since 2019. The dealer claims that the Foster Building cost more than $34 million to build, a substantial difference from previous reports that listed the price simply as more than $20 million.

Sperone invested more than $15 million personally in the building, using funds from the sale of a Roy Lichtenstein—the most valuable artwork in his collection, he says—and his apartment in New York.

The dealer says that his investment in the gallery “generates practically no income or dividends,” and adds that it has been “unprofitable and has burned its cash reserves in recent years.”

To back up this claim, the petitioners attached a financial analysis of the gallery’s revenue, profit, and cash reserves from 2019 through December 11, 2025. It shows losses in five of those seven years, including a shortfall of $2.07 million in 2025. Revenue peaked at $20 million in 2021, but dropped to $3.58 million in 2025, according to the documents.

The dispute between the octogenarian partners “is no longer whether the Corporation will physically close down—its Gallery is closed, and the Foster Building is being marketed for sale—it is how the Corporation will wind down and be lawfully dissolved,” John Cahill, the attorney for Sperone and Sandstown, says in the latest filing.