This post was originally published on this site.

Out recently with his granddaughter in Bourg-lès-Valences, a quiet little town in southern France, a pensioner was surprised to hear a loud noise coming from a row of lock-up garages. Tracing the sound to one of them, he opened the door: trapped inside were a 35-year-old woman and her 67-year-old mother.

“I had just come to take my car when I heard women banging and screaming,” the man told BFMTV, a television news station. “I opened the door and two women came out; they were a little dirty. I was happy, they said thank you.”

The mother and daughter, who have not been named, had spent 30 hours in the garage. They had been seized early on February 5 from their home in Saint-Martin-le-Vinoux, a village just over 50 miles away.

The 35-year-old is a magistrate but, surprisingly, she was targeted not because of her own work, but rather that of her partner, a business associate in a cryptocurrency start-up.

The women were victims of a crime wave sweeping France of what is known as “wrenching”, kidnapping people (or members of their families) who have made fortunes with bitcoin or similar cryptocurrencies. The perpetrators then demand massive ransoms, often running into millions of pounds, to be paid in the digital asset.

It was the eighth attack reported in the country since the start of this year, far more than the rest of the world put together, and compares with 20 during the whole of 2025. Some 70 to 80 people are due to go on trial in France in the coming months accused of participation in such crimes, which often involve extreme violence.

Britain has not been spared: last November, a group of masked men climbed inside a car in Oxford carrying two men and three women and forced one of their victims to transfer £1.5 million of cryptocurrency. Six months earlier, Jacob Irwin-Cline, an American tourist, claimed to have had $123,000 of crypto currencies stolen after being abducted and drugged by a fake Uber driver who picked him up from a Soho bar.

The problem is on a far greater scale in France, according to Éric Larchevêque, a big name in the world of cryptocurrency and a star of the Qui veut être mon associé? [Who wants to be my partner?], the French version of Dragon’s Den.

“Right now in France setting up a kidnapping costs just €20-30,000, because small-time thugs are willing to do it for €2,000 or €3,000,” he told me. “There is a huge pool of people who’ve basically gone off the rails and are ready to do anything for money, with zero morals. And the justice system isn’t feared at all. It is way too lenient.”

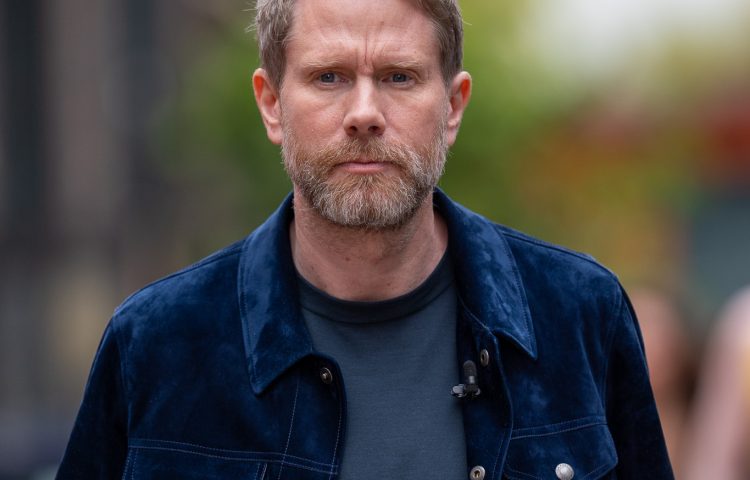

Éric Larchevêque

FRANCK JEANNIN

Larchevêque knows from personal experience the horrors of which some gangs are capable. In January last year, he was contacted by a group claiming to have kidnapped David Balland, a friend and business partner, and his wife, Amandine. They demanded a ransom of €10 million (£8.7 million) to be paid in cryptocurrency.

He immediately alerted the police and, at their suggestion, began to negotiate with the kidnappers. “The goal was to buy time for the investigators to track down David and Amandine,” he said.

Then matters took a dramatic turn for the worse. A few hours later he was sent a video that showed them severing one of Balland’s fingers. “It actually showed the act,” Larchevêque said. “We realised it was becoming extremely serious. The case was escalated to a very high level and all possible resources were deployed to make finding David the top priority.”

David Balland

Talks went on for some 48 hours, during which time he even sent them €3 million in crypto, which was later blocked by the authorities. The next day, the couple, who had been taken to separate locations, were freed by the GIGN, an elite unit of the gendarmerie that specialises in hostage situations. They have declined to speak publicly about their ordeal until after their captors’ trial, the date of which has not yet been set.

A few months later, the father of a man who had made a fortune in cryptocurrencies was also kidnapped by four masked men in Paris, and held for 58 hours, during which time he, too, had a finger severed. He was eventually freed by police.

In another even more brazen attack a fortnight later, three masked men tried to bundle a 34-year-old woman, out with her two-year-old son in the east of the city, into the back of their van. The woman, whose father heads a cryptocurrency exchange, was saved by her partner, who fended them off:

Larchevêque, the author of a recent best-selling book on cryptocurrencies, said that such kidnappings tend to be ordered from abroad. Balland’s, for example, is thought to have been masterminded by Badiss Mohamed Amide Bajjou, 24, a Franco-Moroccan, who was arrested last June in Tangiers.

The dirty work is then typically carried out by petty criminals recruited via Telegram or other messaging apps who are paid just a few thousand euros each for carrying out the crime.

Badiss Mohamed Amide Bajjou

In most cases the victims are thought to be selected via lists showing their wealth that circulate on the so-called “dark web”, a centre for criminal activities. There have also been at least two cases in which gangs have been passed information about people’s personal finances by government employees.

Official figures in France, as elsewhere in the world, are likely to understate the true number of attacks, according to David Sehyeon Baek, a cybercrime and cybersecurity consultant, who has watched the growth of the phenomenon globally from his base in the Asia-Pacific region.

He said: “Victims often have incentives to keep the situation quiet, including fear of tax scrutiny and reputational damage, and, most importantly, fear of retaliation once criminals have demonstrated they know the home address and family details.

“Organised crime adapts quickly when it sees a repeatable model that can generate large payouts with low technical barriers.”

For the gangs, the main attraction of demanding bitcoin is the ease of getting payment. “In the old days someone paying a ransom had to bring along a bag of money, which made the kidnappers vulnerable when they came to pick it up,” said a senior policeman who has dealt with such cases. “Now a simple text message is enough. But the action remains the same. It’s just the form of the ransom that has changed.”

Yet experts have said that criminals are wrong to think the money is untraceable. Sehyeon Baek said: “Transactions are recorded on a public ledger, which means investigators and blockchain analytics firms can often follow flows, especially when funds hit regulated exchanges or identifiable services.”

In the case of the women in the garage, six people, including a minor, were arrested last weekend after a massive police operation involving 160 officers. Two of them were captured as they tried to board a bus to Spain. They were brought to Paris and formally charged on Wednesday. No ransom appears to have been paid.

Despite the success of such police operations, Larchevêque believes the only way to tackle the problems is through far tougher punishments for kidnappers. This would, in turn, lead them to demand more money for carrying out jobs.

“It’s a business, and if the cost of organising a kidnapping goes from €30,000 to €400,000 there will be far fewer of them,” he said. He has also argued that France’s strict gun rules should be relaxed to allow those at risk to protect themselves.

In the meantime, Larchevêque is spending heavily on private security for himself and his family. “It’s not that I am living in a bunker that I never leave, but we have to have close protection, which is tough,” he said. “I don’t want to run the risk of my wife or children being kidnapped.”