This post was originally published on this site.

Beijing

—

For China, the record $1.2 trillion annual trade surplus its authorities reported Wednesday is resounding proof of the resilience of its economy in the face of US trade friction.

But the historic figure also tells another story: one of the far-reaching potential for China’s massive export engine to reshape the global economy – and help Beijing win more leverage in its rivalry with the United States.

Whether or not that engine can keep going at the speed that it has – with its 2025 surplus jumping 20% over the previous year’s – is uncertain and depends on the extent to which countries continue to throw up trade barriers against Chinese goods.

But analysts say that even if the growth of the surplus (a measure of how much more a country exports than it imports) slows in the year ahead, the major drivers of China’s expanding role as the world’s manufacturing superpower – and its massive global outflow of goods – are unlikely to.

China’s trade juggernaut has already showed its capacity to adapt, with its exporters swiftly pivoting from US consumers toward emerging markets in Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America after US President Donald Trump kicked off a tit-for-tat tariff war with Beijing early last year.

And the staggering surplus figure is also testament to the country’s rapid climb to dominate green technologies like EVs, lithium-ion batteries, and solar panels, as well as its prowess in making machinery and tech products at scale.

The influx of those goods into markets across the world – especially as fierce competition and weak demand in China has meant companies need to export to survive – has been welcomed in some markets, and led to deep frictions with others, who say subsidized Chinese goods are crushing domestic competition.

But viewed from Beijing, those trade dynamics have been a significant source of confidence for Chinese officials – especially in their relations with the US.

US-China trade frictions

China’s trade resilience throughout the year – despite seeing a 19.5% drop in annual exports to the US, its long time largest single export market – defied expectations and allowed Beijing to show that it can survive even with reduced access to the world’s richest consumers.

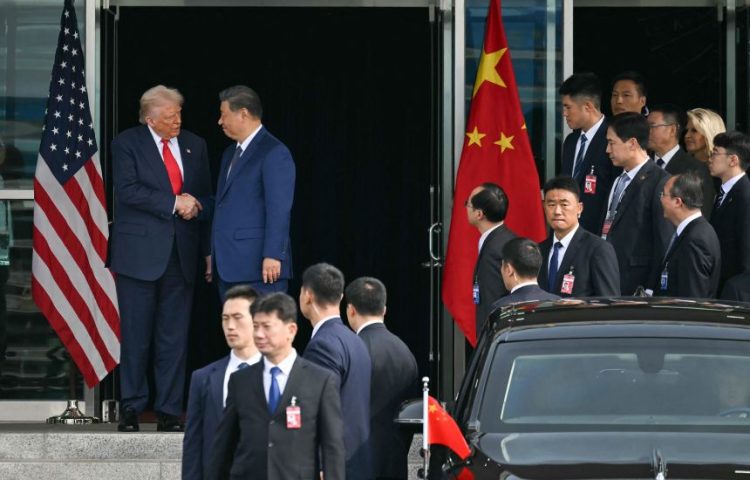

That will give Beijing less appetite for big concessions as the US and China continue to negotiate their economic ties – including during a potential trip from Trump to China in April.

Currently tariffs imposed last year on Chinese goods into the US stand at 20%, down from the triple-digit levels they had risen to briefly as tensions flared last year. And that could always change: Trump on Monday said countries that do business with Iran will face a new 25% tariff, which could again subject China, a key economic lifeline for the regime in Tehran, to elevated duties.

But past the bilateral relationship, China’s growing foothold as the world’s manufacturer also has more far-reaching consequences for Washington, analysts say, especially in terms of the US’ ability to detangle its strategic supply chains from China.

That’s because the competitiveness of Chinese goods is reducing other countries’ incentives to produce. The Trump administration may aim to bring more manufacturing back to the US, but it will also look to other trusted partners – and if more economies become reliant on China, Washington has fewer options as it tries to reduce its own reliance too, experts say.

“If Germany, France, Japan and (South) Korea were to lose industrial capacities, that will make a supply chain that’s free of Chinese components that much more difficult to achieve,” said Victor Shih, director of the 21st Century China Center at the University of California San Diego.

“We are on the road toward that, and that may well be the reality in the world in the next 10 years … (and the US) may need to make even more concessions as China’s dominance over various supply chains increases over time.”

Barriers to entry

Already a number of countries have thrown up protections of their own.

Alongside the US, Canada has put in place hefty barriers that essentially block Chinese electric vehicles from their markets; Mexico last month approved sweeping new tariffs on imports from on a handful of countries, including China.

But earlier this week, the European Union moved toward an option to replace existing tariffs on Chinese-made EVs, by setting out the conditions under which China-based EV makers can commit to sell at minimum prices in Europe.

And analysts say that countries, including smaller developing markets, may be more wary of irking China, even to protect the growth of their own manufacturing sectors – especially when contending with a US trade war.

“It’s really hard to simultaneously deal with problems coming with imports from China at the same time you’re dealing with the problems of your exports to the United States,” said Jacob Gunter, head of the economy and industry program at the MERICS think tank in Berlin, who is researching how countries are responding to the issue of Chinese overcapacity undermining domestic industry.

“Everyone is utterly terrified about the rare earth and the other export controls that China has shown its ability to wield. Until they develop alternative sources for those things, it’s very hard to go fight a trade war against China,” he added.

Consumption slump

China has defended its trade practices and pushed back against the idea that it is flooding global markets with artificially cheap products and a glut of production that’s often referred to as “industrial overcapacity.”

An AI cartoon put out by Chinese state media Xinhua last month used a singing cartoon eagle to accuse critics of a double standard, with the lyrics: “when we lead its ‘progress wow,’ when China leads its ‘overcapacity now.’”

Other media outlets and pundits in China have hailed the trade surplus as a sign of the country’s deep involvement in globalization and of resilience in the face of a Western push to “de-risk” supply chains from China.

But there is also a deep awareness within the country of the other side of the economy’s reliance on exports: a persistent slump in domestic consumer demand.

That means the strong impetus to export that has helped China keep its economic growth on track in the face of US frictions, also belies a deeper dependence on the global economy than Beijing would like.

And there are voices in China being frank about that risk.

“An excessively high surplus indicates a reliance on external demand for economic growth,” said an editorial last month in Nanfang Daily, the Communist Party newspaper of Guangdong province, one of China’s key manufacturing powerhouses.

“If global market demand fluctuates or external conditions change, it may pose potential risks to the stability of the domestic economy,” it added.

CNN’s Joyce Jiang contributed to this report.