This post was originally published on this site.

A sanctioned oil tanker has for the first time established a direct geographic link between Russia’s Arctic “shadow fleet” and oil product exports to Venezuela, connecting two of the world’s most sensitive energy and sanctions flashpoints, according to ship-tracking and trade data.

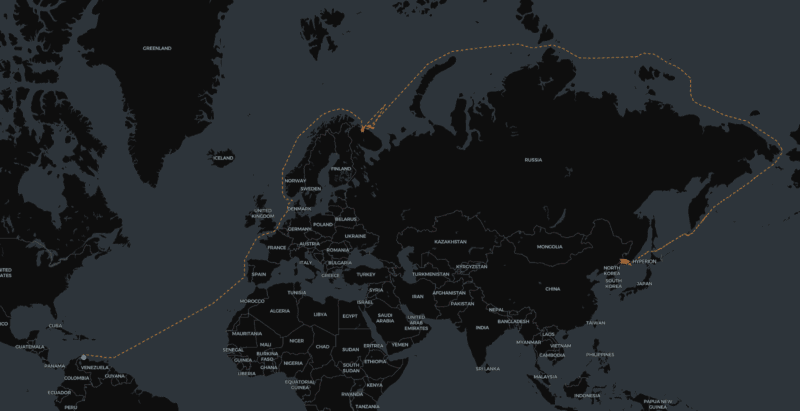

The Gambian-flagged tanker Hyperion arrived this month at Venezuela’s Amuay terminal, part of the country’s largest refining complex, after loading naphtha in Murmansk, data from commodities tracking firm Kpler showed.

The voyage marks the first known case of a shadow fleet vessel operating both in the Russian Arctic and in waters off Venezuela, analysts said.

The development is significant because Hyperion had earlier transited the Northern Sea Route, sailing from the Far East to Murmansk earlier this summer. That Arctic passage, combined with its subsequent Caribbean voyage, establishes a continuous operational footprint linking Russia’s polar export routes with Venezuela’s energy sector. Records also show the sanctioned vessel calling in Zhoushan, China earlier in 2025.

Russia has increasingly relied on a shadow fleet of aging tankers, often operating under flags of convenience and opaque ownership, to move oil and refined products outside Western sanctions, including via the Arctic shortcut.

Venezuela, itself subject to extensive U.S. restrictions, has similarly turned to non-Western shipping and intermediaries to sustain fuel imports and exports.

Hyperion’s movements may heighten scrutiny from Washington. The tanker has already been sanctioned by the United States, the European Union and the United Kingdom, and its call at Venezuela adds a new layer of exposure at a time when the Trump Administration has stepped up enforcement actions, including boarding and detaining vessels linked to sanctioned trade with Caracas.

Hyperion sailed the Northern Sea Route with only an Ice2 ice classification, below the higher standards typically associated with Arctic navigation. At the time of the transit, the ship was flagged by Comoros, according to a Russian maritime database, before later reflagging to Gambia. The Equasis database indicates both flags as “false.”

The Arctic passage underscores the growing flexibility – and risk tolerance – of shadow fleet operators as Russia seeks to monetise energy exports despite sanctions. It also highlights the expanding geographic scope of such vessels, which are no longer confined to a single theatre but now bridge regions separated by thousands of nautical miles.

For energy and security officials, the Hyperion case illustrates how sanctions-evasion networks are becoming increasingly interconnected. By linking Russia’s Arctic export infrastructure with Venezuela’s refining system, the voyage brings together two geopolitical hotspots long monitored separately, raising fresh questions about enforcement, maritime safety, and the resilience of global sanctions regimes.

Subscribe for Daily Maritime Insights

Sign up for gCaptain’s newsletter and never miss an update