This post was originally published on this site.

A week ago I wrote about the possibility that the world would pull its money out of the United States of America:

I noted the rise in the price of gold as a sign that the world might be entering a time of international financial anarchy:

[G]old’s volatility and limited supply might not stop it from becoming the world’s reserve asset once again. In fact, although the dollar is holding its own against other national currencies, its share of global reserves is falling steeply once you bring gold into the picture:

Bloomberg reports that governments and private investors are both buying gold at rapid rates, and that fear of the Trump administration’s policies is a big reason why…[T]he world may be preparing for a time of financial anarchy — an era in which the U.S. is no longer a safe haven and the dollar is no longer the reserve currency, but where China has chosen not to step up to fill the void, and Europe and other powers are unable to do so.

A lot of people asked me whether gold’s rise as a share of reserves was due to people putting their money into gold, or to gold going up in price. In fact, those are the same thing. When demand increases for gold, it means that investors buy more gold, and it also means that the price goes up. So basically, this all means that investors have been demanding more gold.

Anyway, I thought that the idea of “international financial anarchy” was worth expanding on. A lot of people have this vague idea that the world’s finances are based on the U.S. dollar, but they don’t really know exactly what that means, and they don’t know what it would mean for the dollar to lose that status. In fact, people are right to be a little confused, because there are basically a few different ways that the dollar matters to the international financial system:

-

A lot of countries and companies make payments in dollars.

-

A lot of countries hold dollar-denominated assets (like U.S. government bonds) as reserves.

-

A lot of banks and other companies use dollars as collateral for lending.

For a long time, the dollar has been predominant in all of these use cases, leading people to think that these are all the same thing. But they’re not. So when we think about “international financial anarchy”, we should think about how the dollar’s role might change for all of these uses.

Anyway, I don’t have one big grand thesis about the direction in which the international financial system is heading. But the events of the past few weeks have provoked a few thoughts.

One clear lesson of the past few weeks — and of the past two years — is that people still view gold as a safe haven in times of international uncertainty. Here’s a chart of gold’s price:

Gold rose in the pandemic, but it didn’t really take off until 2024. This wasn’t because of U.S. inflation, which was coming down rapidly at the time. In fact, we don’t know exactly why gold started going up; we just know that a bunch of central banks started buying it. Maybe they knew something we didn’t.

But we do know that when Donald Trump came back to power and started doing unpredictable stuff — high tariffs, threats to invade Greenland, threatening the independence of the Federal Reserve, running up huge deficits, and so on — a bunch of investors around the world, especially in Asia, started buying a lot of gold. The Economist reports:

In recent years central banks in emerging markets, led by China, fuelled the [gold] rally. Such hyper-conservative investors have fallen back in love with physical gold, which they hope will protect them amid geopolitical turmoil. Yet flows into gold exchange-traded funds (ETFs) suggest a new group of investors are catching the bug, lured by returns and diversification rather than safety…Asian investors are leading the way. In the past two years holdings of gold by Asia-based ETFs have more than tripled…Big funds in Japan and South Korea likewise logged hefty increases.

Here’s a longer explainer from Bloomberg. Key excerpts:

[A]s an asset without a counterparty, gold doesn’t rely on the success and creditworthiness of a company or state, unlike most financial securities…Soaring government debt around the world has also shaken investors’ trust in sovereign bonds and currencies. In what’s been dubbed the debasement trade, a large number of investors have flocked to gold, silver and other precious metals, seeking a store of value…as public finances deteriorate…

Investors have been closely watching the outlook for inflation in the US, too, as Trump piles pressure on the Fed to bend to his will and cut interest rates. Gold, which pays no interest, typically becomes more attractive in a lower-rate environment, as the opportunity cost of holding it versus interest-earning assets decreases.

More fundamentally, gold’s value is based on people’s beliefs about gold’s value. A lot of people think that gold will take over the global financial system if people lose confidence in national currencies — possibly because in the past, when nations and their currencies weren’t very strong or dependable, and electronic payments weren’t possible, gold was the best way of making international payments.

So when there’s higher expected inflation, or international turmoil, etc., those people — who we typically call “goldbugs” — buy gold. Other investors buy gold in this situation too, because they anticipate demand from goldbugs.

But why gold? It isn’t the only asset whose use doesn’t depend on national governments. There are a bunch of other metals around (in fact, silver also rose in price along with gold). And then there’s Bitcoin, whose value is backed not by national governments, but by an algorithm and an internationally distributed set of “miners” who spend electricity and computing power on carrying out Bitcoin transactions.

For a long time, Bitcoin proponents — including the “maximalists” or “maxis” who think Bitcoin would take over the entire global financial system — argued that the cryptocurrency had become a form of “digital gold” whose natural scarcity and independence of national governments offered investors a safe haven when fiat currencies looked rocky.

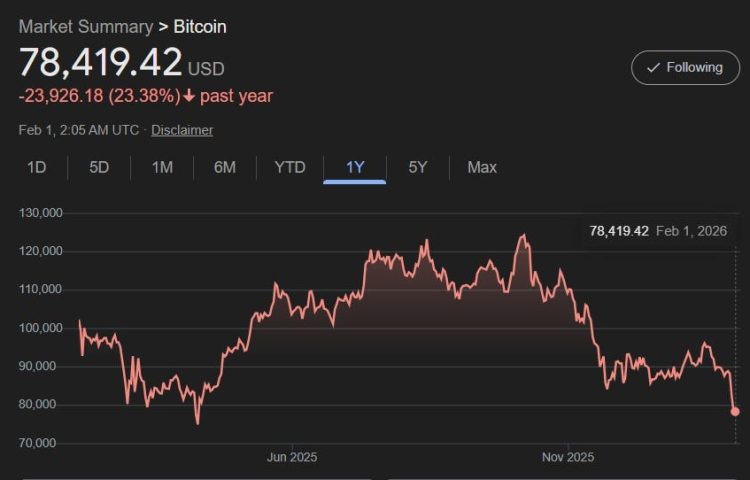

But that story has taken a big hit in recent months. When investors started losing confidence in the U.S. dollar, they also sold Bitcoin, causing the price to plunge:

More broadly, Bitcoin hasn’t shown gold-like behavior over the past few years; instead, it’s more correlated with the U.S. stock market.

This probably tells us something about how investors think about gold versus Bitcoin. They probably think of Bitcoin as something that benefits from the success of the American economy — probably because when the U.S. economy does well and Americans are feeling rich, they put some of their money into Bitcoin. Whereas they still think of gold as something that you need when nations as a whole do poorly.

Ultimately, safe-haven assets are a coordination game — people just sort of collectively decide which assets to buy in order to protect themselves from international financial anarchy. So far, they’re still coordinating on gold, not on Bitcoin.

That said, there’s no guarantee that gold will keep going up. In fact, there was a big gold selloff (and silver selloff) on Friday:

This could have just been because the gold binge was overdone, or because Trump’s reported nomination of Kevin Warsh — a hard-money sort of guy — to lead the Fed after Powell tempered expectations of dollar debasement.

In any case, what gold’s abrupt plunge shows is that an anarchic, gold-based international financial system will probably be inherently less stable than the dollar-based system has been. A lot of people — including the goldbugs — think that gold’s natural scarcity and independence from central bank meddling make a gold-based economy inherently stable. But the fact that no large, trustworthy entity manages the gold price actually means that it’s subject to rapid swings like the one that happened on Friday. And if global payment and collateral systems were based on gold, those price swings would be disruptive to those systems as well.

Goldbugs are thus right about gold’s durable safe-haven status, but they’re not right that this is a good thing. Gold isn’t a superior system — it’s a desperate fallback for a world in which the people who were in charge of the superior system abdicated their duties.

Important changes to the international financial system didn’t start when Trump returned to power. The Ukraine War was also an important event. The return of great-power conflict drove some people to put their money into gold, of course. But in addition, the U.S. and Europe put big financial sanctions on Russia — essentially, cutting Russian banks and other Russian companies out of the international financial system, including the SWIFT payment system. The idea was to make it a lot harder for Russia to pay for imports, thus putting pressure on Putin to end the war.

How much financial sanctions actually succeeded in harming Russia is a matter of debate. But they scared a lot of countries, including China, because those countries realized that their reliance on the dollar-based financial system for their international transactions represented a vulnerability — a pressure point that the U.S. could use on them in the event of a conflict. So they started working on alternative payment systems.

China, for example, accelerated its efforts to develop yuan-based payments systems. The Fed’s Bastian von Beschwitz had a good primer on those efforts. As a result, the share of China’s cross-border payments denominated in yuan started rising:

And the share of global payments done in yuan started rising shortly afterwards:

Even countries generally friendly to America, like India, have been looking to do something similar.

The question is whether this affects the dollar’s position as the global reserve currency. A lot of people seem to think that the use of the dollar for payments forces a lot of companies around the world to hold a bunch of dollars (or liquid dollar-denominated assets) in order to be able to settle their payments.

But is this really true? In the modern age, it’s not very hard to get dollars on the spot if you need them. If an Indian bank wants to make a payment to a Chinese bank, it’s not too hard for the Indian bank to just go to the international currency market and swap some rupees for dollars and hand them to the Chinese bank, who can easily go right back to the currency market and swap the dollars for yuan. Nobody in this story is really holding dollars for very long. So payments that are settled and denominated in dollars don’t seem like they create much demand for dollars in this day and age.

In fact, before the recent Trump-induced drop in the dollar, the U.S. currency had actually gained in strength since the Russia sanctions sent countries in search of alternative payment systems:

The dollar’s share of global foreign currency reserves didn’t take much of a hit from the Ukraine War, either.

“Not much” dependence of dollar reserves on dollar payments doesn’t mean “zero”, of course. In March 2020 when the Covid panic hit, there was such a disruption in the currency market that for a very short while it became hard to get enough dollars to do international payments. Banks around the world hold a few dollars (or liquid dollar-denominated assets) as a hedge against this happening to them again, which does create a little bit of demand for dollars.

This is why the proliferation of non-dollar payment systems still might represent a kind of preparatory stage for countries around the world to dump the dollar. If you don’t have to go through dollar swaps in order to make payments, you don’t even have to think about whether the sudden lack of dollars in your country’s domestic financial system will disrupt your financial plumbing.

And if a country like China were preparing to try to dethrone the dollar as the reserve currency, it would probably start off with replacing the dollar in its payments systems, simply because it’s easy and relatively non-disruptive to do so. Which is why a lot of people are talking about China’s yuan-based payments as part of an attempt to “dethrone the dollar”.

This brings us to the question of whether China is preparing to have the yuan replace the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

Besides shifting toward yuan-denominated payments, China is also stocking up on a lot of gold. Here’s The Kobeissi Letter:

China continues to stockpile gold behind the scenes…China acquired +10 tonnes of gold in November, ~11 times more than officially reported by the central bank, according to Goldman Sachs estimates…Similarly, in September, estimated purchases reached +15 tonnes, or 10 times more than officially reported…Furthermore, China officially bought an additional 0.9 tonnes in December, pushing the total gold reserves to a record 2,306 tonnes…This also marked the 14th consecutive monthly purchase…Assuming official purchases were 10% of what China is actually buying, this suggests China acquired +270 tonnes of physical gold in 2025.

For now, that looks like part of the general shift toward global financial anarchy. But it could also indicate that China is preparing to replace the dollar-based global system with one based on its own currency.

There would actually be precedent for this. In the early 20th century, the global reserve currency shifted from the British pound to the U.S. dollar. Chitu, Eichengreen, and Mehl (2012) show that this mostly happened before 1929. A big driver was World War I, where the UK was a big borrower and the U.S. was a big lender. This resulted in a big flow of gold from the UK to the U.S. That flow intensified during the Depression and then in World War 2. After the war, the dollar had completely replaced the pound as the reserve currency, as formalized by the Bretton Woods agreement. This coincided with the U.S. owning up to three quarters of the world’s gold.

So if the world goes through a transitory period of financial anarchy, in which the dollar is temporarily replaced by gold, China might conceivably stabilize things by buying up much of the world’s gold and using this to make the yuan the reserve currency — if everyone uses gold and China owns the gold, it’s easier to convince the world that the yuan is as good as gold. China’s vast economic heft would, of course, be another powerful argument.

One problem with this theory, however, is that China has shown absolutely no sign of wanting to do this. In fact, they’ve recently been intervening to make their currency cheaper, which requires selling yuan:

This is almost certainly being done as a way to pump up Chinese exports. China is still struggling with a real estate bust, and the government has decided that exports are a way to cushion the impact on the real economy. But the WSJ’s Peter Landers reports that some Chinese people are having second thoughts about the weak yuan:

Several influential [Chinese] economists have recently argued that a meaningful strengthening of the yuan would turbocharge consumption and get China out of its economic doldrums…Liu Shijin, a longtime top economic adviser to the government, said in a speech this month that the U.K. and U.S. also started out as primarily manufacturing powers with puny currencies but eventually matured beyond that stage…

“We should aim for a basic balance between imports and exports” and push for a strong, globally used currency, Liu said…“Chinese consumers can use the same amount of renminbi to enjoy more high-quality, affordable international products, thereby truly realizing the goal of becoming a strong consumer nation,” he said…His comments echoed those of a former People’s Bank of China official, Sheng Songcheng, who said in November that the correct exchange rate to balance the purchasing power of Chinese and American consumers might be as strong as five or even four yuan to the dollar instead of seven today…

Such views are spreading widely among economists in China but haven’t become official doctrine[.]

Landers suggests that a stronger yuan and a weaker dollar might help the U.S. revitalize its manufacturing industry, by reducing the trade deficit. Trump might embrace that idea. But Paul Krugman is very skeptical that this will help much:

Any way I cut it, the dollar’s reserve currency status is only part of the explanation of U.S. trade deficits. Even more important, trade deficits account for only a small fraction of the decline in manufacturing as a share of our economy…Many people assert that the answer is the dollar’s role as the preeminent reserve currency. But as I tried to argue…this story doesn’t hold up when you look at it closely…[T]rade deficits are, in fact, responsible for only a fairly small fraction of the long-run decline in the manufacturing share…

Germany’s surpluses are much larger as a share of its own GDP than China’s. Yet Germany has also seen a huge long-term decline in the manufacturing share of employment…If Germany’s huge trade surpluses haven’t been enough to avoid a big shift away from manufacturing, even ending U.S. trade deficits (which Trump’s tariffs won’t achieve) wouldn’t make us a manufacturing-centric economy again…

Last year the U.S. ran a manufactures trade deficit of around 4 percent of GDP. Suppose we assume that this deficit subtracted an equal amount from spending on U.S. manufactured goods. In that case what would happen if we somehow eliminated that deficit?…Well, it would raise the share of manufacturing in GDP — currently 10 percent — by less than 4 percentage points, because manufacturing firms buy a lot of services. A rough estimate is that manufacturing value-added would rise by around 60 percent of the change in sales, or 2.5 percentage points, implying that the manufacturing sector would be around a quarter larger than it is[.]

I also recommend Krugman’s interview with Maurice Obstfeld on this topic.

History also doesn’t offer much encouragement here. The UK’s loss of the reserve currency during the World Wars didn’t revitalize its manufacturing sector at all; in fact, the UK became a manufacturing midget, and runs chronic trade deficits driven by huge imports of manufactured goods.

So while the shift to a China-centric global financial system would probably be good for regular Chinese people, it would probably not do much to reindustrialize America. If we want that to happen, we should look to industrial policy rather than to currency policy.